This post explains why Jens von Bergmann and I made a map of renter density across Metro Vancouver. If you think this post is tl, and you dr, you can click here to see the map.

It’s hard to avoid the effects of the housing crisis in Metro Vancouver. Available rental units are few and far between, with rents that are out of reach for a huge proportion of the region’s population. The high cost of land and construction puts a tight squeeze on groups trying to provide an alternative to market housing. Even those that securely own a home have given up on the idea that their grandkids might be able to live in the neighbourhood.

And that’s just for the fortunate. For others, the threat of homelessness looms constantly. This threat goes by two words in our local lexicon: renoviction and demoviction. Both mean essentially the same thing for the victim: find a new place, fast, in a market where almost nothing is available. Of course – that’s not easy, and not always possible. It’s a dark game of musical chairs.

Renters should have better legal protections in the case of a renoviction or demoviction. Current provincial legislation underplays the trauma of an eviction, and makes no attempt to fairly compensate tenants for their trouble or get them a comparable place at the same rent.

We should also be building new housing units at least as quickly as the region’s population grows. The only coherent alternative to this is some kind of system that prevents people from moving to Metro Vancouver, which would be disastrous for civil rights, our economy, etc. The new housing that gets built should be a wide mix of tenures, including social housing, supportive housing, co-housing, co-operatives, rental housing, rooming houses, employer-built housing, and literally everything in between. Preferably, we would allow for more non-speculative housing than needed to depress the market and put more power into tenants’ hands.

But where should these new homes go? Time for a thought experiment.

You are a social housing agency, and you want to build a much-needed new social housing development. Almost every piece of land in Metro Vancouver is already occupied by blueberry farms, apartment towers, Whitespots, and everything in between. Every new thing will displace someone or something.

Imagine you could pick any piece of land in the region. What will you choose to displace? There is no way around this question, but it should be relatively easy to answer, right?

Displacing different types of land uses can cause different amounts of harm. Would you choose a piece of land that causes the least amount of harm? I would.

Here is my interpretation of what “least harm” means:

1. New homes should not go on protected land.

Some may argue that new affordable homes should be build on protected agricultural or forested land. This is the argument that “urban sprawl” is, on balance, good for society. That may provide more housing in the short term, but the potential ecological damage is severe, and this will impact humans in the long run. And as we all know, the ill-effects of environmental damage will always be felt more by the underprivileged in society.

2. New homes should not displace residents of purpose-built rental or non-market housing.

Doing so would be a recipe for homelessness. And if they do get displaced, tenants need a lot more protection than they get today.

3. New homes should be in places that allow for access to the things that people need.

Cities are great because they allow you to live close to a lot of things that you might need: food, jobs, family, medical care, education, etc. People that live in new homes should be able to take advantage of these things. And they should have at least two viable options for getting around: transit, active transportation, carsharing, etc.

The Map

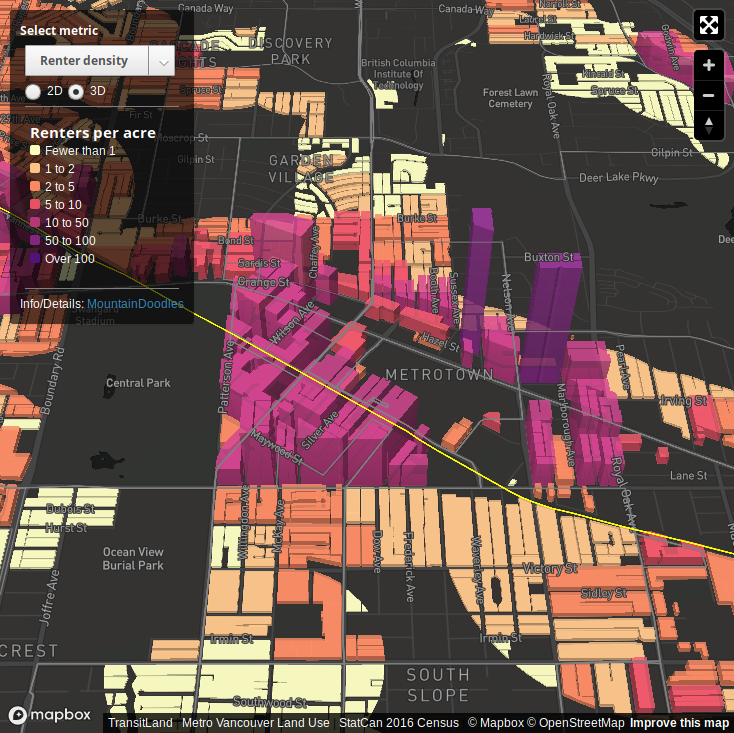

All of these things are easily mappable, so Jens and I made a map of Metro Vancouver that would indicate the “least harmful” places to put new housing.

- Areas in grey are excluded because they are either auto-oriented, protected, or occupied by some other land use (industrial, commercial, institutional, etc.). [Note: Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ communities are also excluded from the map because of census data issues.]

- Areas in beige, peach, and salmon have decent transportation options (criteria defined on Jens’ blog) but few renters per acre. These are the “least harmful” places for more housing – few, if any, renters will be displaced if development happens on this land.

- Areas in magenta and purple have more renters per acre, and development in these areas pose a greater risk of displacing renters.

Motivation

The tragedy of the demovictions at Metrotown forced me to think through and clarify my thoughts on housing. I have always thought that it is good to put dense housing near transit, and I still do. But at what cost? This map makes crystal-clear how to avoid demovictions while still building housing with good transportation options. The apartment blocks at Metrotown clearly have 10-50 renters per acre. The good news is that there is lots of good land with few renters on that map.

I was deeply inspired by the tenants in Metrotown. When faced with demoviction, they offered an inspiring way forward. They developed a grassroots land use plan that showed how to build new housing (which we definitely need) while treating renters with respect. It is an absolute must-read for anyone in the urbanism world.

This is their “Three Stage Plan for Development Without Displacement” (paraphrased):

- Upzone single family neighbourhoods near Metrotown to allow for non-market, medium-density housing

- Move current rental tenants out of Metrotown apartment buildings, and into these new buildings

- Replace Metrotown apartment buildings with denser non-market housing, and allow former tenants to move back into these new buildings.

The neighbourhoods that the Peoples’ Plan identifies for redevelopment have between 0.5 and 4 renters per acre, literally a tenth of theirs. So I would say those neighbourhoods are great candidates for re-development. Nonetheless, renters in low-density areas should have the same protections as everyone else, and ideally they would be re-housed as part of the same “three stage plan”.

So how did you answer the thought experiment above? Maybe you thought commercial land should have been included? If you had a different answer (and some coding skills), you are able to create an altered version of the renter density map using the source code that Jens posted on Github.

Denis Agar is a transportation planner, new dad, and settler on the unceded, ancestral territories of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ peoples.